Strolling through noisiness and periodic functions.

Stepping on Cracks Fairly 🔗

Whenever I walk down a sidewalk, I have a hard time not thinking about stepping on the cracks. Specifically, I like for my left and right foot to step on a crack the same amount of times. I don’t completely obsess over it, but it’s always somewhere between the front and back of my mind.

When I was on a walk earlier today, it was closer to the front. I made an exaggerated step with my right leg to extend my gait and find a crack where my right foot would land - evening up the crack tally between legs. As I made that step, I began to wonder if you could enumerate the number of crack steps during a walk. At first pass it seemed plausible: your foot size is fixed, your gait is (mostly) fixed, and the distance between cracks is (once again, mostly) fixed. I evenly crack-stepped home and got out the notepad.

The Sidewalk as a Periodic System 🔗

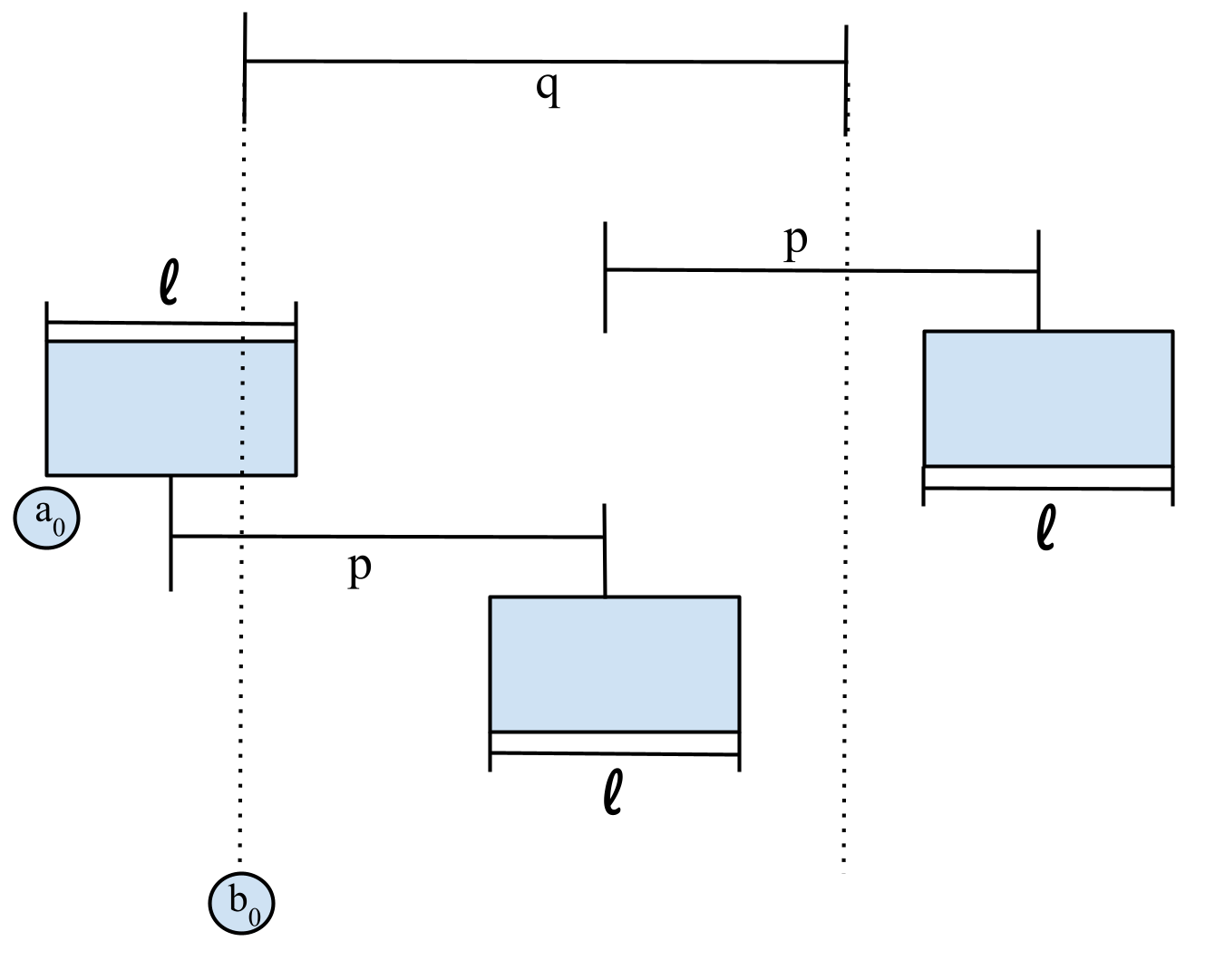

Here’s the way I drew it up:

Each box is a foot with length $l$, and the steps start at point $x = a_0$. Each step has length $p$ (the gait). The cracks start at point $x = b_0$ and they have a distance of $q$.

Now that the problem is laid out, we can see that we’ve got two periodic systems with periods $p$ and $q$. This means that the entire system has a combined period which is $LCM(p,q)$. Consider a gait of 3 ($p = 3$) and crack distance of 4 ($q = 4$). At the point $x = 12$ along the axis, everything starts back over and repeats exactly what it just did.

The question becomes what just happened between $x = 0$ and $x = 12$? Turns out, that needs to be calculated by hand. I’ve uploaded the script I wrote to do exactly that on my GitHub. Because of the periodic nature, though, you can really create any sort of repeating pattern you want. All you have to do is adjust $a_0, b_0, p, q$ and $l$.

For example, imagine a system where every single step lands the middle of one foot right on a crack, hitting a crack 100% of the time. Now shift that over by a bit, and you can hit a crack 0% of the time. You can make systems where only even steps hit cracks, or make a pattern like odd step, odd step, even step, odd step, odd step, even step, … and so on. That pattern, as a side note, is $p=3, l=1.5, q=2.5, a_0=0,$ and $b_0=3.25$.

To summarize, the whole thing is periodic, and once you find what happens in the first period by simulation, the whole system is determined.

Introducing Some Chaos 🔗

As you’ve seen, the problem is essentially some intervals and points placed along a number line, and we want to see how often the intervals contain the points. With fixed periods and interval length, things work out quite neatly with a pattern as discussed.

But what if we introduce some randomization? The first observation we can make is that if the points are randomly placed along the number line, the rate at which they intersect the intervals will converge to $l/p$, or the length of the interval over the period that it repeats. This makes intuitive sense - consider an $l = 1$ interval length and $p=3$ period of reptitions. The amount of the number line covered by the intervals is just $1/3$, so a random smattering of points should hit an interval $1/3$ of the time.

What turned out to be much more interesting, though, is what would happen if some error/noise was introduced into the step length (period) of the intervals. At this point, we can define the intervals as the set of ranges {$[a_0 + kp, a_0 + kp + l]$} for any non-negative $k$. For the back half of the range, we can make it to include some Guassian noise $\epsilon$, which is centered at 0 with a standard deviation $\sigma$. Correspondingly, the next step is calculated iteratively (instead of with the $kp$ term) so that the beginning of the range includes the previous $\epsilon$ and the end of the range once again has more noise introduced.

Essentially, the interval period / step length ($p$) is varying with Guassian noise, but the length of the intervals ($l$) and period of the points / sidewalk ($q$) remain fixed.

Results! 🔗

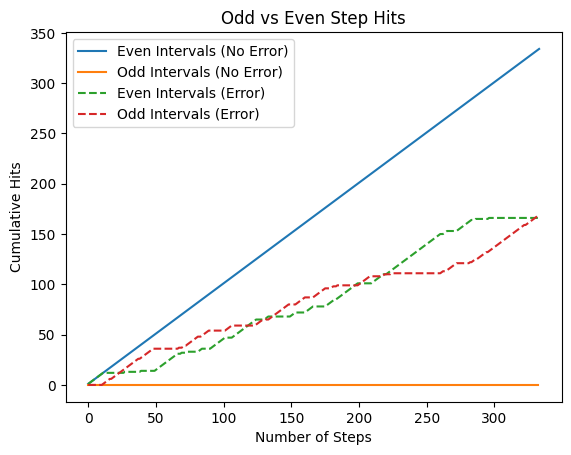

To illustrate the findings, I have used this system: $p=3, l=1, q=2, a_0=0,$ and $b_0=0.5$. The thing to note about this system is that it exclusively lands on even intervals. The system starts on an intersection, the following step is not an intersection, the next step is an interesction, the next step isn’t, and so on. As a result the even steps are the only ones that result in an interesection in the purely periodic system.

Here’s a surprise: when we introduce even a small amount of noise (std = 5% of the interval period), the amount of even and odd intervals that contain points quickly converge to the same(ish) value.

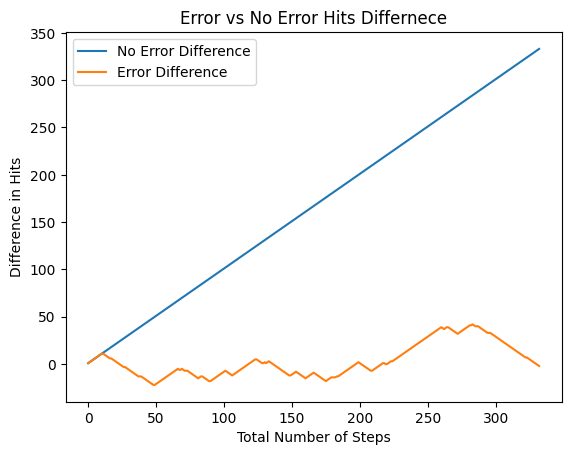

The error completely changes the system. Now, the even and odd interval intersections are equally matched as opposed to completely one-sided. And it happens right off the bat. Here is a similar plot showing the difference between the even and odd interesections:

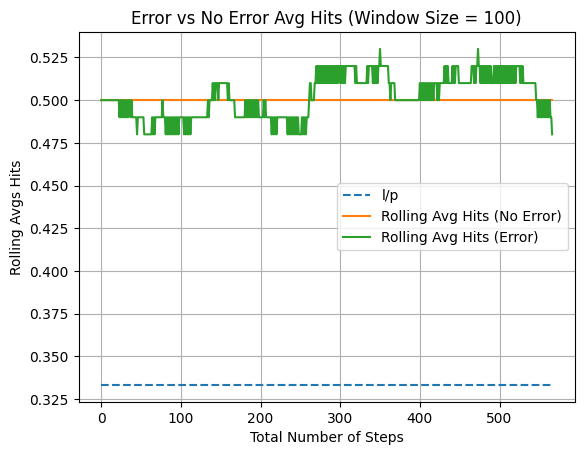

The orange line essentially hovers around 0 from the very beginning. What makes this even more interesting is when we look at the total percentage of the time that an interesection occurs. In the original system without noise, it’s obvious that the “hit rate” is 50% because every even step intersects and every odd step does not. As I mentioned before, however, with a randomized point distribution the hit rate converges to $l/p$, the fraction of the number lined covered by intervals. My assumption was, with the randomness introduced, the hit rate would likely converge to that fraction.

Here is a plot that shows a rolling average of the hit rate for the error-introduced system, and also proves me wrong:

The system with the error maintains the average intersection rate of the system without error! By introducing some Gaussian noise, the intersection rate can be roughly maintained while removing all of the even/odd step bias. It simultaneously acts randomly and periodically!

Back to Fair Stepping 🔗

Ultimately, this is good news for two reasons. First, it is a pretty interesting result about how you can use noise to remove some bias from a system while maintaining its core periodicity. Second, it’s good for those inclined to step fairly on cracks. With only a small amount of variance in your gait, which I assume most people have, you can be confident that the dispersion of crack-steps will be equal between feet - even in a moderate sample size.