Heart rate variability (HRV) is the primary metric that the WHOOP fitness band uses to calculate your recovery. In this article I look at just how much HRV contributes to recovery, plus how a high HRV variance can make things tricky.

What is a WHOOP Recovery Score 🔗

The WHOOP fitness band is a product that tracks your activity throughout the day by measuring primarily your heart rate. In addition, and more importantly, it tracks your recovery during sleep. The WHOOP website (and my personal experience) will tell you HRV is the primary contributer to calculating recovery. What exactly HRV is and why it’s so important is something I surely will explain worse than WHOOP themselves, so find out more about that here.

Luckily WHOOP allows you to export your data, which includes a daily value for the metrics it tracks. These include resting heart rate, blood oxygen %, energy burned in calories, time in bed, light sleep, REM sleep, and more. All of these features, including HRV, are presumably inputs to the model that calculates recovery score. By using this data, something of a crude recreation of the recovery score model can be made. Of course it won’t be perfect, but by using data from both myself and a friend, it suffices to provide some useful insight as to how HRV plays its part.

Investigating the Features 🔗

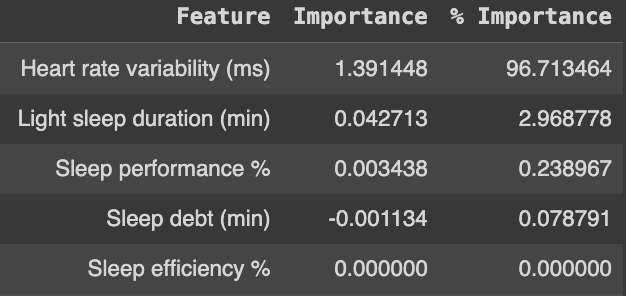

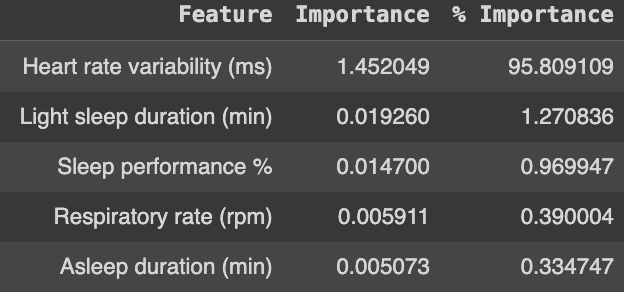

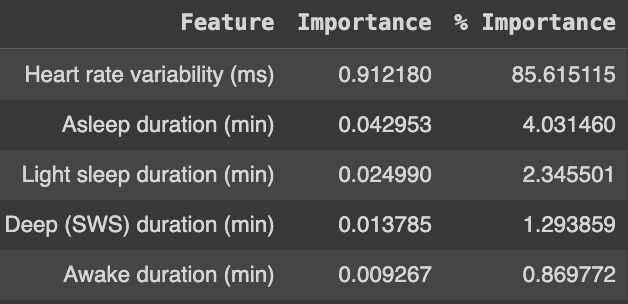

The plan is to create a few models that replicate the WHOOP recovery score well enough, and then investigate how important each of the features were in those models. I make a linear model, a GBM model, and an SVR model and then use permutation importance to look at each of the features. You can see everything in more detail on Github. I don’t link my own data because that feels sort of weird to put online, but if you are a WHOOP user you can put the filepath to your own “phisiological_cycles.csv” from the WHOOP data export.

The results from each model using my personal data set are summarized here:

It’s worth noting the RMSE of the three models was 70, 36, and 36, respectively, which indicatees the WHOOP model was recreated rather effectively.

The (Potential) Problem With a High HRV Variance 🔗

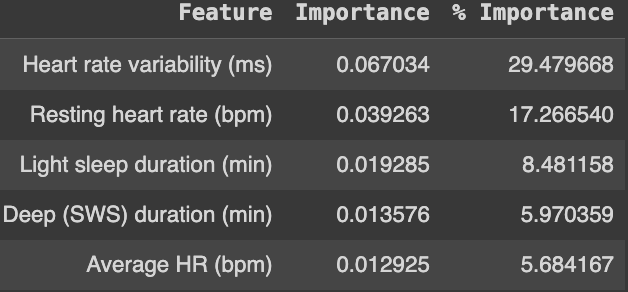

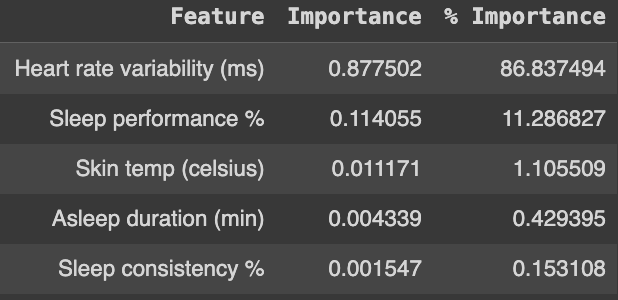

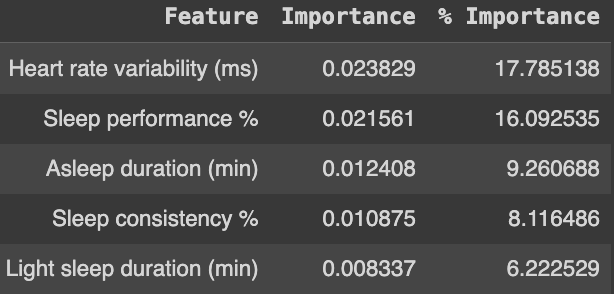

What’s unique, and potentially misleading, about my particular data is that my HRV has a very high variance. I assume this is partially genetic and partially due to, let’s say, lifestyle choices. Because an n=1 sample size is bad practice, I also use another WHOOP user’s data to assemble a doubly robust n=2 sample size. For reference, this WHOOP user’s HRV variance is calculated to be 303.3, whereas mine is 1981.2. I used the same methods as before on the lower variance HRV dataset, and here are the results:

With this data set, the RMSE of the three models was 98, 115, and 115, respectively. What this leads me to believe is that as HRV deviates much higher or much lower than your average, it dominates the recovery score more and more. Hence why the higher variance data set had more success calcuating recovery score - it could rely almost entirely on HRV. When the HRV is not changing so drastically, other factors contribute more which are more difficult to pick up in a recreation of the recovery model.

This discrepancy is what originally led me to conduct this study: I noticed my HRV can hit high extremes, and my recovery would correspondingly be high despite poor or little sleep. But is that an accurate representation of my body’s recovery? Or is it just inflated because the variance of my HRV is greater?

I am sure more considerations are taken into calculating the recovery score than I could possibly be aware of. I would assume that data beyond just one value per day is involved in the model as well. Perhaps the HRV and other features are taken at different points throughout the day which aren’t available in the data export. Regardless, it’s certain a high HRV is the preeminent factor in a good recovery score. Whether or not WHOOP is accurately capturing your body’s recovery if your HRV varies greatly, I’m not as sure.